This post was also published on The Energy Collective on 4/9/2015.

It’s hard to talk about energy. Just ask any science teacher who has tried to define energy in a classroom. People stare blankly when you say, “It’s the ability to do work.” They furrow their brow when you tell them it’s not the same thing as “power.” You lose them completely if you bring up the laws of thermodynamics.

And yet, this thing that defies simple definition is critical to everything we do. Energy is fundamental to all facets of life on Earth. So it’s no surprise that folks who spend their days talking about energy have had to develop a special vocabulary, in order to have concrete discussions about an enigmatic concept.

In particular, if you want to talk about the effect that energy sources have on the environment, there is a large variety of phrases to choose from. Let’s look at a few of them, based on a literal interpretation of the words.

Concerned about pollution? Try clean energy. Afraid of running out of fossil fuels? You probably want renewable energy, or perhaps sustainable energy (more on these later). Is climate change your biggest worry? You may want to promote low-carbon energy. There is also alternative energy, which is attractive to people who know that they don’t like fossil fuels, but don’t want to specify exactly why. Even more vague is green energy, which refers to nothing specific at all and simply labels the person who says it as pro-environment.

Words come and go over time

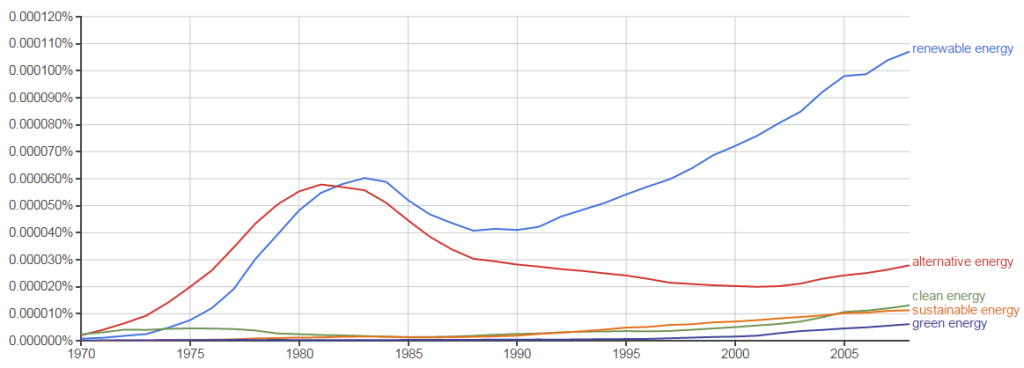

With this long menu of phrases available, you might wonder which ones are used most often. Google Ngram Viewer lets you graph how often a word or phrase has appeared in books written in recent history. Plotting the five phrases below, we see that “renewable energy” has been the forerunner since the late 80’s.

(I wonder happened in the early 80’s to cause publishing on both “renewable” and “alternative” energy to take a temporary dive. If you have thoughts on this, please comment.)

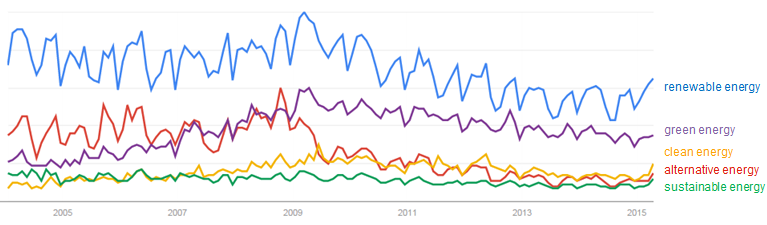

[UPDATED 4/10/2015: Commenter Bruce McFarling on the Energy Collective points out that the 1970’s were a time of increasing oil prices, and thus increasing interest in alternatives to oil. Indeed, the trajectory of inflation-adjusted oil prices bears strong resemblance to the red and blue curves above.]Google Trends data confirm that “renewable energy” is also consistently the preferred term for curious readers. “Green energy” is relatively more prominent in online search than it is in print.

Thinking harder about “renewable”

When it comes to making the public more aware of energy issues, I’m in favor of any and all phrases that motivate people to be conscientious energy consumers. The words “clean,” “green,” “renewable,” “sustainable,” etc. are great ways to remind people of the connection between energy and the environment.

But if you look beneath the surface, there are some important nuances that go into determining the words that experts use to talk about energy. Take nuclear energy, for example. Nuclear fission requires uranium mined from the ground. While the known reserves of uranium are fairly large, we can’t get more uranium after it’s gone, so nuclear energy is not renewable.

Now consider geothermal energy, which is commonly referred to as a renewable energy source. When underground hot water is tapped to generate electricity, the lost heat is then replenished over time from the large reserves of heat inside the planet. (See Chapter 4 of this IPCC special report for some helpful information on geothermal energy.) While the amount of heat stored in Earth’s core is massive (~1031 J), it is also finite. We can’t get more after it’s gone. So is geothermal energy actually renewable?

For that matter, what about solar energy? Solar is considered the epitome of “renewable,” but sunlight itself is also technically a finite resource. Eventually the Sun will turn into a red giant and consume Earth, at which point I’m pretty sure our solar panels won’t work anymore. To avoid this kind of semantic quibbling, many people (especially fans of nuclear energy) prefer the word “sustainable” to describe energy sources which humans could continue to exploit for many, many years.

Sustainability is complicated

Just like “renewable,” the definition of “sustainable” depends on many factors, including the timescale and the rate of resource extraction. If the reserves of a particular resource are very large relative to how much we are using, then its use might be called “sustainable,” because we don’t need to worry about running out any time soon (depending on your definition of “soon”).

But that’s not the end of the story. Sustainability is a higher standard than simply having “enough” of something. Our social, environmental and economic systems are enormously complex, and no one resource can be extracted and used in isolation. To be fairly labeled “sustainable,” our energy usage should not damage or disrupt other important resources, such as the air we breathe or the water we drink.

It is also important to note that “sustainable” can be used as a relative term, just like “clean.” So nuclear energy is both clean and sustainable relative to fossil fuels’ impact on global climate, but it is dirty and unsustainable if you assume that the radioactive waste can not be safely contained.

Ultimately, “renewable” and “sustainable” should only be used to refer to practices of energy use, rather than to permanently label a source of energy. Energy from biomass is not renewable if we consume more biomass than we can produce each year. Burning fossil fuels is sustainable if we do it on a small enough scale.

These subtle distinctions can make it hard to fact-check any claims of sustainability. Luckily, there are tools we can use to analyze how our energy practices mesh with various complex systems. Life-cycle assessment is useful for quantifying the material and energy flows involved in a process, and resilience analysis can help predict the impact that a disturbance will have on an ecosystem. These tools are not perfect, but they are a good starting point as we look for a path forward that can actually be sustained.